Whereas both physical full lotus sitting and mental full lotus sitting involve a sense of subjective effort -- an effort to do, and an effort not to do -- body-and-mind-dropping-off full lotus sitting corresponds to what Alexander described as the right thing doing itself. The right thing doing itself describes something that seems to be happening naturally, effortlessly, spontaneously.

Flowing water or burning wood are examples of things doing themselves spontaneously -- in accordance with the 2nd law of thermodynamics. But, in the same way that a pump may need to be primed before water starts spontaneously flowing, and in the same way that persistence may be required to get a fire going, considerable effort may be required on the part of both Alexander teacher and Alexander student before the student starts to get the experience of the right thing doing itself.

Again, in the same way that a pump may need to be primed before water starts spontaneously flowing, and in the same way that persistence may be required to get a fire going, considerable physical and mental effort may be required on the part of both Zen master and disciple before the disciple starts to get the real experience of full lotus sitting as body and mind dropping off.

Sometimes people who have scant or no experience of Alexander work think that they know what it is all about just from reading about it. Similarly, people who have never met a true Zen master think that they know, on the basis of their reading, without having made the requisite physical and mental effort, what a Zen master means by body and mind dropping off.

So Master Dogen wrote: "There is mental sitting, which is not the same as physical sitting. There is physical sitting, which is not the same as mental sitting. And there is body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting, which is not the same as body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting."

In the former body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting, the sitter forgets himself in the spontaneous flow of sitting.

In the latter body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting, the sitter, having read some words in a book or words on a blog, or having heard some teaching from the mouth of a fame-seeking Zen charlatan, has the idea of losing himself in the spontaneous flow of sitting, or has the idea of all things being one, or has the idea of becoming a self-realized Zen Master, or has some other such romantic idea. (Yes, you who know who you are, I am thinking particularly of you.)

If we understand the above distinction, our instinctive human tendency is to wish not to be in the latter group, that is, the group of pretentious Zen duffers. Our instinctive tendency is to aspire to be in the former group, the group of the truly authentic ones.

In that case, we have already fallen into the trap of trying to be right. Whereas if we were wiser, remembering Master Dogen's teaching that buddhas are enlightened about delusion, we might dare to tiptoe into the territory of the pretentious Zen duffer, and see how the land lies there.

When a human control freak neglects, for a long time, to care about being wrong, how then is full lotus sitting?

Om mani padme hum.

Doesn't Master Dogen make a point of telling us?, in his instructions for sitting-zen: ZEN-AKU OMAWAZU, ZE-HI KANSURU KOTO NAKARE. "Do not think good-bad. Do not care true-false/right-wrong."

Failing to hear these words always seems to be where my trouble starts -- as Marjory Barlow clearly saw, and clearly demonstrated to me. It is very difficult for me to stop worrying about whether I am The True One, or not. Part of the power of Gudo's hold over me was that he led me to believe, in my younger days, that he felt that I would indeed become The True One -- "the most excellent Buddhist master in the world."

This conclusion brings me back full circle to the sentiments I expressed on the opening post of this blog...

The quest for authenticity

And turning of the light

Turns into, all too easily,

Trying to be right,

Which, sure as 2 plus 1 makes 3,

Makes neck and shoulders tight.

Quad Erat Demonstrandum.

In introducing my best friend to the public, incidentally, I was not hoping to attract helpful advice or sympathy from amateur psycho-therapists, fellow Zen masters in their own mind, and the like. My intention has rather been to use this particular blog to help me work out, for the benefit of self and others, the practical implications of what the Alexander midwife Marjory Barlow, in delivering me, repeatedly took pains to remind me.... "Listen, love: being wrong is the best friend you have got in this work."

Om mani padme hum.

Sunday, 30 March 2008

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA: Mental Full Lotus Sitting

What "mental sitting" is I do not know. But Marjory Barlow, Nelly Ben-Or and one or two other teachers of the FM Alexander Technique have given me some clues as to what it is not.

It is not a muscular effort of doing; it is not anchored in feeling; it is not postural self-arrangement or self-organization; it is not reliance on habit; it is not any kind of bodywork; it is not mindless mechanical repetition; and it is not thinking as I have hitherto understood thinking.

Although the kind of mental work that Alexander practised is not thinking as thinking is generally understood, FM Alexander called it "thinking."

To what extent might this kind of thinking be relevant to a buddha's practice of upright sitting? Is it possible to interpret HISHIRYO, or "anti-thinking," not only as physical action that is opposed to thinking, but also, from the dialectically opposite viewpoint, as mental thinking that is opposed to the habitual doing (stemming from faulty feeling, misconceptions, et cetera) that ordinarily governs the body ?

Is it possible to understand HISHIRYO like this, both as an affirmation of action that negates thinking and at the same time as an affirmation of thinking that negates doing?

According to what I was taught by Gudo Nishijima, No! Never! According to Gudo, HISHIRYO must never be interpreted as anything other than a negation of thinking. HISHIRYO means not thinking but action, not thinking but just doing. That was Gudo's strongly-held view.

Master Dogen's instructions for sitting-zen, however, include the sentence that "It is vital to bring about an opposition between the ears and the shoulders, and an opposition between the nose and the navel." (MIMI TO KATA TO TAISHI, HANA TO HESO TO TAISESHIMEN KOTO O YOSU).

How is it possible to bring about such an opposition? Is it possible, by direct muscular intervention, by doing something, to bring about a movement ears and shoulders away from each other? No, it is not. What muscular effort can do is pull the shoulders and ears towards each other. For direct muscular intervention to succeed in pulling ears and shoulders apart, there would need to be muscular attachments joining ears to the ceiling and joining shoulders to the walls on either side. Bringing about an opposition between ears and shoulders requires not direct muscular effort but rather muscular release, not doing but rather undoing.

My Alexander head of training, Ray Evans, used to say that we know more about the mechanisms of muscular effort (i.e. "doing") whereas the mechanisms of release (or "undoing") are less well understood.

Marjory Barlow used to emphasize, "You cannot do an undoing." When I started working with Marjory, she caused me to understand that, despite 15 years of sitting-zen practice under Gudo Nishijima, and two years of Alexander teacher training, I was still wrongly of the view that I might be able to do an undoing. So Marjory often reminded me, "You cannot do an undoing."

A further 11 years of Alexander work since my first lesson with Marjory have still not equipped me with a definitive view of what "mental sitting" is, but I have been caused to be able to see, on a good day, what it is not.

It is not muscular effort. It is not what I know. It is not my misguided effort to arrange myself symmetrically. Above all, it is not doing. On the contrary, it is diametrically opposed to doing, just as doing is diametrically opposed to thinking.

Have I thus just expressed a view on what "mental sitting" is? If so, I did so, not for the first time, in error. Whenever I decide upon a view on what "mental sitting" is, which I frequently do, it always turns out to be... not that.

I do not know what Master Dogen meant by "mental sitting." What I do know is that the prejudice I used to hold against what I perceived as sissy mental practice, was just the stupid prejudice of an unenlightened person.

The question I have addressed above is not how to become buddha, and not how to cultivate the empty field. The question here is not even how to take the backward step of turning light and shining. The question is just how to practise mental sitting. That is the question Master Dogen posed 750 years ago.

Understanding that the work of FM Alexander poses the same question, I came back to England to train as an Alexander teacher. And so, as my day job in England, I teach people who are sitting to think up from their sitting bones. But that does not mean that I know what thinking up is, any more than a plumber knows what water is.

Inevitably, I have my views and opinions about what FM Alexander meant by "thinking," and about what Master Dogen meant by "mental full lotus sitting," but those views and opinions always turn out to be mistaken.

Still, since I came to France with the intention of making mistakes, let me conclude this post by deliberately making a big one:

To practise mental full lotus sitting means, for example, to think the ears and shoulders apart, and to think the head out from the pelvis. Not to do it; just to think it.

It is not a muscular effort of doing; it is not anchored in feeling; it is not postural self-arrangement or self-organization; it is not reliance on habit; it is not any kind of bodywork; it is not mindless mechanical repetition; and it is not thinking as I have hitherto understood thinking.

Although the kind of mental work that Alexander practised is not thinking as thinking is generally understood, FM Alexander called it "thinking."

To what extent might this kind of thinking be relevant to a buddha's practice of upright sitting? Is it possible to interpret HISHIRYO, or "anti-thinking," not only as physical action that is opposed to thinking, but also, from the dialectically opposite viewpoint, as mental thinking that is opposed to the habitual doing (stemming from faulty feeling, misconceptions, et cetera) that ordinarily governs the body ?

Is it possible to understand HISHIRYO like this, both as an affirmation of action that negates thinking and at the same time as an affirmation of thinking that negates doing?

According to what I was taught by Gudo Nishijima, No! Never! According to Gudo, HISHIRYO must never be interpreted as anything other than a negation of thinking. HISHIRYO means not thinking but action, not thinking but just doing. That was Gudo's strongly-held view.

Master Dogen's instructions for sitting-zen, however, include the sentence that "It is vital to bring about an opposition between the ears and the shoulders, and an opposition between the nose and the navel." (MIMI TO KATA TO TAISHI, HANA TO HESO TO TAISESHIMEN KOTO O YOSU).

How is it possible to bring about such an opposition? Is it possible, by direct muscular intervention, by doing something, to bring about a movement ears and shoulders away from each other? No, it is not. What muscular effort can do is pull the shoulders and ears towards each other. For direct muscular intervention to succeed in pulling ears and shoulders apart, there would need to be muscular attachments joining ears to the ceiling and joining shoulders to the walls on either side. Bringing about an opposition between ears and shoulders requires not direct muscular effort but rather muscular release, not doing but rather undoing.

My Alexander head of training, Ray Evans, used to say that we know more about the mechanisms of muscular effort (i.e. "doing") whereas the mechanisms of release (or "undoing") are less well understood.

Marjory Barlow used to emphasize, "You cannot do an undoing." When I started working with Marjory, she caused me to understand that, despite 15 years of sitting-zen practice under Gudo Nishijima, and two years of Alexander teacher training, I was still wrongly of the view that I might be able to do an undoing. So Marjory often reminded me, "You cannot do an undoing."

A further 11 years of Alexander work since my first lesson with Marjory have still not equipped me with a definitive view of what "mental sitting" is, but I have been caused to be able to see, on a good day, what it is not.

It is not muscular effort. It is not what I know. It is not my misguided effort to arrange myself symmetrically. Above all, it is not doing. On the contrary, it is diametrically opposed to doing, just as doing is diametrically opposed to thinking.

Have I thus just expressed a view on what "mental sitting" is? If so, I did so, not for the first time, in error. Whenever I decide upon a view on what "mental sitting" is, which I frequently do, it always turns out to be... not that.

I do not know what Master Dogen meant by "mental sitting." What I do know is that the prejudice I used to hold against what I perceived as sissy mental practice, was just the stupid prejudice of an unenlightened person.

The question I have addressed above is not how to become buddha, and not how to cultivate the empty field. The question here is not even how to take the backward step of turning light and shining. The question is just how to practise mental sitting. That is the question Master Dogen posed 750 years ago.

Understanding that the work of FM Alexander poses the same question, I came back to England to train as an Alexander teacher. And so, as my day job in England, I teach people who are sitting to think up from their sitting bones. But that does not mean that I know what thinking up is, any more than a plumber knows what water is.

Inevitably, I have my views and opinions about what FM Alexander meant by "thinking," and about what Master Dogen meant by "mental full lotus sitting," but those views and opinions always turn out to be mistaken.

Still, since I came to France with the intention of making mistakes, let me conclude this post by deliberately making a big one:

To practise mental full lotus sitting means, for example, to think the ears and shoulders apart, and to think the head out from the pelvis. Not to do it; just to think it.

Saturday, 29 March 2008

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA: Bodily Full Lotus Sitting

This and the next two posts are not intended as a contribution to the body-mind problem in philosophy. I am reporting back on a 25-year endeavour, filled from beginning to end with trouble and strife, to respond in everyday life to Master Dogen's exhortation to practise -- bodily, mentally, and as body and mind dropping off -- full lotus sitting.

In Shobogenzo chapter 72, Zanmai-o-zanmai, The Samadhi That Is King of Samadhis, Master Dogen writes: SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi.

In the Nishijima-Cross translation of 1997, the sentence is translated "Sit in the full lotus posture with the body."

I first read Gudo Nishijima's own translation of the chapter Zanmai-o-zanmai in 1982 or 1983, and the chapter made a terrific impact on me.

In 1986 I read the original Japanese text of the chapter for the first time. That was a very exciting and rewarding moment.

SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi has five Chinese characters, read as SHIN (body), KEK (full), KA-FU (cross-legged) and ZA (sitting). No and subeshi are written in Japanese kana. The word no is a joining particle, and subeshi means "should do."

SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi.

"We should practise physical full cross-legged sitting."

Notice that there is originally no word corresponding to the English word "posture." Originally the imperative is not to sit in a posture; the imperative is more dynamic: the imperative is to practise sitting; in short, to sit.

So that might be the first mistake I made in translation. I introduced the problematic concept of "posture" when in Master Dogen's original text there is no such concept at all.

The understanding around posture that I had before was based on what I now regard as an erroneous view: namely, that there is such a thing, in sitting-zen, as "right posture."

In the post previous to this, I mentioned Raymond Dart and the so-called "Dart double spirals." When a person's sitting lacks symmetry, undue tightness in one or both of these myofascial spirals is generally implicated (as also an immature asymmetrical tonic neck reflex is often implicated) in the asymmetry. A structural integration practitioner named Thomas Myers, building on the work of Raymond Dart, wrote as follows in his book Anatomy Trains:

Homage to midwives everywhere, who know the value that lies in developmental processes...

Om. She of the Jewel in the Lotus! Hum.

Om mani padme hum.

I quote and praise the above paragraph not because the bodyworker Thomas Myers is espousing a view that I believe to be true, but rather because the human being Thomas Myers seems to be expressing, on the basis of his experience of trying to help others, the dropping off an old view. The old view is a view about right, symmetrical posture as some static thing that it might be valuable for a human being to achieve -- as if time might then stand still, as if the 2nd law might then cease to operate. To hold that old, static, posture-affirming view has also been my mistake.

Another big mistake I make is to assume that I know what Master Dogen meant by SHIN no ZA, bodily sitting.

I used to feel confident, as a rugby player, and as a martial artist, as somebody who was accustomed to laying his body on the line, that I understood well what Master Dogen meant when he wrote of sitting as a physical act, sitting with the body. But the understanding that I held before of Master Dogen's words SHIN no ZA, "bodily sitting," I now no longer hold with the confidence that I used to have.

I tend to assume that my body, like the bodies of others, is something bulky, heavy, massive, and that in order to get this body up off the sofa or up off the floor, an effort of doing is necessary. Weighed down by the conception of a heavy body, the physical act of sitting upright becomes something akin to weightlifting -- the making of a physical effort to defy gravity.

From 1994 onwards Alexander work began to challenge my view of what kind, and how much, effort is required to keep a body upright. Alexander work began to challenge my old view, and then, in a similar way to what Master Dogen does to views in Shobogenzo, Alexander work proceeded to batter my old view into submission.

In order to investigate more deeply what Master Dogen meant by "bodily sitting," it might be necessary to investigate more deeply what Master Dogen meant by the dialectically opposite conception of "mental sitting." It is because it has been demonstrated to me, in the context of Alexander work, that I don't know how to sit mentally, that I begin also to doubt my habitual conception of what it is to sit bodily.

In these days of holistic hairdressing, the oneness of body and mind is a generally accepted concept -- just the kind of concept, in other words, that Master Dogen himself always took pains to batter into submission.

Such is the unconsidered viewpoint, equally, of the holistic hairdressers and the so-called Zen masters of the present day.

Master Dogen did not subscribe to this viewpoint. He wrote that there is mental sitting that is not the same as physical sitting, and there is physical sitting that is not the same as mental sitting.

To clarify this teaching exactly -- not for body-mind philosophers but just for fellow devotees of sitting-zen --

might be the main purpose of my life.

The interpretation that I heard from Gudo of Master Dogen's teaching of physical sitting vs mental sitting, was this: "physical" means when the parasympathetic nervous system is in the ascendancy, i.e, when we are body-conscious (e.g. during a post-lunch dip in arousal), and "mental" means when the sympathetic nervous system is in the ascendancy, i.e. when we are mind-conscious (e.g. when our will has been aroused by excited discussion). Thus, the difference between physical sitting and mental sitting, like every other problem in Buddhist philosophy, can be reduced back to the state of the autonomic nervous system.

This was Gudo's view.

What can I say?

All I have to offer is understanding, albeit partial, of my own wrongness. In my everday life, despite my physical effort to sit upright in lotus four times per day, I wobble from extreme parasympathetic lethargy to extreme sympathetic anger. I roam constantly through the six samsaric realms. My vestibular system is more dysfunctional than most. Views that I have held about this, that, and the other, have all too often turned out to be mistaken. The trendy view on the oneness of body and mind, which for many years I also unthinkingly subscribed to, has turned out to be just another one of those mistaken views.

Master Dogen wrote: SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi; "Practise bodily full lotus sitting."

In assuming that I knew in the past what Master Dogen meant, I was wrong. If I assume now that I know what Master Dogen meant, again, I am very liable to be wrong.

In Shobogenzo chapter 72, Zanmai-o-zanmai, The Samadhi That Is King of Samadhis, Master Dogen writes: SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi.

In the Nishijima-Cross translation of 1997, the sentence is translated "Sit in the full lotus posture with the body."

I first read Gudo Nishijima's own translation of the chapter Zanmai-o-zanmai in 1982 or 1983, and the chapter made a terrific impact on me.

In 1986 I read the original Japanese text of the chapter for the first time. That was a very exciting and rewarding moment.

SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi has five Chinese characters, read as SHIN (body), KEK (full), KA-FU (cross-legged) and ZA (sitting). No and subeshi are written in Japanese kana. The word no is a joining particle, and subeshi means "should do."

SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi.

"We should practise physical full cross-legged sitting."

Notice that there is originally no word corresponding to the English word "posture." Originally the imperative is not to sit in a posture; the imperative is more dynamic: the imperative is to practise sitting; in short, to sit.

So that might be the first mistake I made in translation. I introduced the problematic concept of "posture" when in Master Dogen's original text there is no such concept at all.

The understanding around posture that I had before was based on what I now regard as an erroneous view: namely, that there is such a thing, in sitting-zen, as "right posture."

In the post previous to this, I mentioned Raymond Dart and the so-called "Dart double spirals." When a person's sitting lacks symmetry, undue tightness in one or both of these myofascial spirals is generally implicated (as also an immature asymmetrical tonic neck reflex is often implicated) in the asymmetry. A structural integration practitioner named Thomas Myers, building on the work of Raymond Dart, wrote as follows in his book Anatomy Trains:

It is very important to note here that there is no virtue involved in having a symmetrical, balanced structure. Everyone has a story, and without doubt the most interesting and accomplished people I have had the pleasure and challenge to work with have had strongly asymmetrical structures. In contrast, some people with naturally balanced structures face few internal contradictions, and as a result can be bland and less involved. Assisting someone with a strongly challenged structure out of their pattern toward a more balanced pattern does not make them less interesting, though perhaps it will allow them to be more peaceful or less neurotic or to carry less pain. Just, at this juncture, let us be clear that we are not assigning any ultimate moral advantage to being straight and balanced. Each person's story, with so many factors involved, has to unfold and resolve, unfold and resolve, again and again over the arc of a life. It is our privilege as structural therapists to be present for, and midwives to, the birth of additional meaning within the individual's story.

Homage to midwives everywhere, who know the value that lies in developmental processes...

Om. She of the Jewel in the Lotus! Hum.

Om mani padme hum.

I quote and praise the above paragraph not because the bodyworker Thomas Myers is espousing a view that I believe to be true, but rather because the human being Thomas Myers seems to be expressing, on the basis of his experience of trying to help others, the dropping off an old view. The old view is a view about right, symmetrical posture as some static thing that it might be valuable for a human being to achieve -- as if time might then stand still, as if the 2nd law might then cease to operate. To hold that old, static, posture-affirming view has also been my mistake.

Another big mistake I make is to assume that I know what Master Dogen meant by SHIN no ZA, bodily sitting.

I used to feel confident, as a rugby player, and as a martial artist, as somebody who was accustomed to laying his body on the line, that I understood well what Master Dogen meant when he wrote of sitting as a physical act, sitting with the body. But the understanding that I held before of Master Dogen's words SHIN no ZA, "bodily sitting," I now no longer hold with the confidence that I used to have.

I tend to assume that my body, like the bodies of others, is something bulky, heavy, massive, and that in order to get this body up off the sofa or up off the floor, an effort of doing is necessary. Weighed down by the conception of a heavy body, the physical act of sitting upright becomes something akin to weightlifting -- the making of a physical effort to defy gravity.

From 1994 onwards Alexander work began to challenge my view of what kind, and how much, effort is required to keep a body upright. Alexander work began to challenge my old view, and then, in a similar way to what Master Dogen does to views in Shobogenzo, Alexander work proceeded to batter my old view into submission.

In order to investigate more deeply what Master Dogen meant by "bodily sitting," it might be necessary to investigate more deeply what Master Dogen meant by the dialectically opposite conception of "mental sitting." It is because it has been demonstrated to me, in the context of Alexander work, that I don't know how to sit mentally, that I begin also to doubt my habitual conception of what it is to sit bodily.

In these days of holistic hairdressing, the oneness of body and mind is a generally accepted concept -- just the kind of concept, in other words, that Master Dogen himself always took pains to batter into submission.

Because body and mind are one, there is no difference between physical sitting and mental sitting. There is only sitting itself which, viewed from one side is physical and viewed from the opposite side is mental. "Body" and "mind" are two faces of one coin.

Such is the unconsidered viewpoint, equally, of the holistic hairdressers and the so-called Zen masters of the present day.

Master Dogen did not subscribe to this viewpoint. He wrote that there is mental sitting that is not the same as physical sitting, and there is physical sitting that is not the same as mental sitting.

To clarify this teaching exactly -- not for body-mind philosophers but just for fellow devotees of sitting-zen --

might be the main purpose of my life.

The interpretation that I heard from Gudo of Master Dogen's teaching of physical sitting vs mental sitting, was this: "physical" means when the parasympathetic nervous system is in the ascendancy, i.e, when we are body-conscious (e.g. during a post-lunch dip in arousal), and "mental" means when the sympathetic nervous system is in the ascendancy, i.e. when we are mind-conscious (e.g. when our will has been aroused by excited discussion). Thus, the difference between physical sitting and mental sitting, like every other problem in Buddhist philosophy, can be reduced back to the state of the autonomic nervous system.

This was Gudo's view.

What can I say?

All I have to offer is understanding, albeit partial, of my own wrongness. In my everday life, despite my physical effort to sit upright in lotus four times per day, I wobble from extreme parasympathetic lethargy to extreme sympathetic anger. I roam constantly through the six samsaric realms. My vestibular system is more dysfunctional than most. Views that I have held about this, that, and the other, have all too often turned out to be mistaken. The trendy view on the oneness of body and mind, which for many years I also unthinkingly subscribed to, has turned out to be just another one of those mistaken views.

Master Dogen wrote: SHIN no KEKKAFUZA su beshi; "Practise bodily full lotus sitting."

In assuming that I knew in the past what Master Dogen meant, I was wrong. If I assume now that I know what Master Dogen meant, again, I am very liable to be wrong.

Friday, 28 March 2008

In Denial On Denial

The three sentences that, as regular followers of my blogging will know, I regard as central to the whole of Master Dogen's teaching in Shobogenzo are:

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

SHINJIN DATSURAKU NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

Bodily practise full lotus sitting.

Mentally practise full lotus sitting.

As body and mind dropping off, practice full lotus sitting.

I am getting around to writing three posts in which I shall endeavor to pinpoint how I have misunderstood what Master Dogen meant in writing these three sentences.

Meanwhile, perhaps by way of a catharsis that may help to clear my mind in preparation for this task, I would like to write something about denial, inspired by an observation I heard yesterday on Radio 4's In Our Time. The theme was the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, and one of the contributors drew a comparison between (a) the response to Henry's attack, of the Roman catholic church in England, and (b) the response to the Nazi holocaust, of Jews in Europe.

That response, as I understand it from my own experience, has to do with fear paralysis/shock/denial.

When Yoko Luetchford visited Gudo Nishijima at his office in 1997, she made an issue of certain footnote entries in Shobogenzo Book 3. In one footnote, for example, in connection with the sentence "We should sit like coiled dragons," I had included a reference to the discoveries of Professor Raymond Dart, an anatomist who identified two swathes of muscle and fascia forming a double spiral around the torso. In another footnote, I had made a reference to the anti-gravity reflexes.

Those entries could have simply been deleted, without causing me any offence, because I had given the publisher (Windbell) permission to edit the footnotes freely without consulting me -- but this permission most certainly did not extend to the translation text itself, as everybody involved well knew. If Gudo had felt that "the continuing upwardness of buddha" was a duff translation, as with hindsight I agree it was, all he had to do was ask me to change it back. But, no, a decision was taken that I would not be consulted. Why?

The purpose of Mrs Luetchford's visit was to persuade Gudo that I had an agenda to, in his words, "identify Buddhism with AT theory." And Gudo's response to this was, again in his own words, "strong refusal."

What that "strong refusal" meant in practice was something akin to the attitude of Henry VIII or Adolf Hitler to their own perceived enemies within. From 1997 onwards Gudo began to see me as a threat, a danger, a potential enemy of his "real Buddhism."

My response to that situation was, pure and simple, denial. I failed to respond appropriately to what was happening because what was happening was beyond my capacity to take it in. So I took refuge, sometimes totally sometimes only partially, in denial. Taking refuge in denial, I went to Japan in 1998 and received Gudo's Dharma.

After the ceremony, Gudo asked me to promise that I wouldn't adulterate the Dharma with other teachings. He never stopped suspecting, even then, that my agenda was to adulterate the Buddha-Dharma with "AT theory."

Three years ago when Gudo told me his concern that James Cohen was out take control of our Shobogenzo copyright, I asked Gudo simply to entrust his half of the copyright to me, and thereby to show his trust in me. I saw it as an opportunity for Gudo to redeem himself. Gudo's first response was that of course he trusted me. How could I, after all these years, doubt it? I replied that when a man asks a woman to marry him, what he wants to hear is not reassuring words like "I love you" or "I trust you." What he wants to hear is simply "Yes" followed by "I do." In that spirit I was asking for entrustment of the copyright, as an action. So then Gudo agreed that, yes, he would give me the copyright. But then like a bride having second thoughts, he emailed me a day or two later to say that, no, in fact he could not do that. This really deeply challenged my ability to remain in denial. But somehow I was able to cling to the illusion that Gudo might be testing me.

Then came our blog wars. When Gudo called me a "non-Buddhist," I looked for irony in his words. When Gudo announced that I was excluded from Dogen Sangha, when I was barred from posting on his blog, I took those things again as a kind of test. Even when Gudo announced that Brad Warner was his successor, I still somehow retained a trace of hope that Gudo would somehow redeem himself.

But then the final clincher came, unexpectedly, not from another inimical act but rather from an attempted act of kindness on Gudo's part. Earlier this year he sent me a cheque for $1800, as my half of the royalties for the POD version of Shobogenzo that he and some of his Dharma-heirs (Cohen, Rocca et al) had gone ahead with without my agreement. He expressed his wish that I would share his happiness that the Shobogenzo project, which had cost Gudo so much of his own money over the years, had finally turned a profit. Looking at the cheque, and reading the letter, then I could see, undeniably, that Gudo, in expecting that I might be happy to receive the cheque, had totally and utterly failed to read my mind.

If my master perceives some wrong agenda in me, how can I be sure that I am not, unconsciously, harbouring some such agenda? I cannot be sure. But if my master perceives that my mind is such that I might be happy to receive a cheque for 1800 tainted dollars, then it is beyond even my capacity to deny that the old man, somewhere along the way, totally lost the plot.

Before sending me the cheque Gudo emailed me to let me know that he wanted to send it. My reply concluded with the wish that Gudo might use the cheque to line his coffin and go to hell. Nevertheless, while I was in France in February, the cheque duly arrived in the post. When I got back to England, I put the cheque and letter back in their envelope, wrote on it "PLS RETURN TO SENDER," trudged heavily to the postbox at the end of my road, and sent the letter back.

The truth is that what was poisoned in 1997 was not only the Nishijima-Cross translation partnership but also the mutual trust between father and son. When Gudo reacted to Mrs Luetchford's visit with his "strong refusal," it was not only that a son lost his father but also that a father lost his son.

That is why today, while listening to Desert Islands Discs and eating my breakfast, I found myself cupping my face in my hands and sobbing -- allowing Moro (II) to try to do is job of kick-starting into action a system that has long been stuck in fear paralysis/denial.

That is why, on Saturday morning when I was pointing a wall and Danny Boy came on the radio, my eyes became so blurred that I was in danger of falling off the ladder.

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

SHIN NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

SHINJIN DATSURAKU NO KEKKAFUZA SUBESHI.

Bodily practise full lotus sitting.

Mentally practise full lotus sitting.

As body and mind dropping off, practice full lotus sitting.

I am getting around to writing three posts in which I shall endeavor to pinpoint how I have misunderstood what Master Dogen meant in writing these three sentences.

Meanwhile, perhaps by way of a catharsis that may help to clear my mind in preparation for this task, I would like to write something about denial, inspired by an observation I heard yesterday on Radio 4's In Our Time. The theme was the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII, and one of the contributors drew a comparison between (a) the response to Henry's attack, of the Roman catholic church in England, and (b) the response to the Nazi holocaust, of Jews in Europe.

That response, as I understand it from my own experience, has to do with fear paralysis/shock/denial.

When Yoko Luetchford visited Gudo Nishijima at his office in 1997, she made an issue of certain footnote entries in Shobogenzo Book 3. In one footnote, for example, in connection with the sentence "We should sit like coiled dragons," I had included a reference to the discoveries of Professor Raymond Dart, an anatomist who identified two swathes of muscle and fascia forming a double spiral around the torso. In another footnote, I had made a reference to the anti-gravity reflexes.

Those entries could have simply been deleted, without causing me any offence, because I had given the publisher (Windbell) permission to edit the footnotes freely without consulting me -- but this permission most certainly did not extend to the translation text itself, as everybody involved well knew. If Gudo had felt that "the continuing upwardness of buddha" was a duff translation, as with hindsight I agree it was, all he had to do was ask me to change it back. But, no, a decision was taken that I would not be consulted. Why?

The purpose of Mrs Luetchford's visit was to persuade Gudo that I had an agenda to, in his words, "identify Buddhism with AT theory." And Gudo's response to this was, again in his own words, "strong refusal."

What that "strong refusal" meant in practice was something akin to the attitude of Henry VIII or Adolf Hitler to their own perceived enemies within. From 1997 onwards Gudo began to see me as a threat, a danger, a potential enemy of his "real Buddhism."

My response to that situation was, pure and simple, denial. I failed to respond appropriately to what was happening because what was happening was beyond my capacity to take it in. So I took refuge, sometimes totally sometimes only partially, in denial. Taking refuge in denial, I went to Japan in 1998 and received Gudo's Dharma.

After the ceremony, Gudo asked me to promise that I wouldn't adulterate the Dharma with other teachings. He never stopped suspecting, even then, that my agenda was to adulterate the Buddha-Dharma with "AT theory."

Three years ago when Gudo told me his concern that James Cohen was out take control of our Shobogenzo copyright, I asked Gudo simply to entrust his half of the copyright to me, and thereby to show his trust in me. I saw it as an opportunity for Gudo to redeem himself. Gudo's first response was that of course he trusted me. How could I, after all these years, doubt it? I replied that when a man asks a woman to marry him, what he wants to hear is not reassuring words like "I love you" or "I trust you." What he wants to hear is simply "Yes" followed by "I do." In that spirit I was asking for entrustment of the copyright, as an action. So then Gudo agreed that, yes, he would give me the copyright. But then like a bride having second thoughts, he emailed me a day or two later to say that, no, in fact he could not do that. This really deeply challenged my ability to remain in denial. But somehow I was able to cling to the illusion that Gudo might be testing me.

Then came our blog wars. When Gudo called me a "non-Buddhist," I looked for irony in his words. When Gudo announced that I was excluded from Dogen Sangha, when I was barred from posting on his blog, I took those things again as a kind of test. Even when Gudo announced that Brad Warner was his successor, I still somehow retained a trace of hope that Gudo would somehow redeem himself.

But then the final clincher came, unexpectedly, not from another inimical act but rather from an attempted act of kindness on Gudo's part. Earlier this year he sent me a cheque for $1800, as my half of the royalties for the POD version of Shobogenzo that he and some of his Dharma-heirs (Cohen, Rocca et al) had gone ahead with without my agreement. He expressed his wish that I would share his happiness that the Shobogenzo project, which had cost Gudo so much of his own money over the years, had finally turned a profit. Looking at the cheque, and reading the letter, then I could see, undeniably, that Gudo, in expecting that I might be happy to receive the cheque, had totally and utterly failed to read my mind.

If my master perceives some wrong agenda in me, how can I be sure that I am not, unconsciously, harbouring some such agenda? I cannot be sure. But if my master perceives that my mind is such that I might be happy to receive a cheque for 1800 tainted dollars, then it is beyond even my capacity to deny that the old man, somewhere along the way, totally lost the plot.

Before sending me the cheque Gudo emailed me to let me know that he wanted to send it. My reply concluded with the wish that Gudo might use the cheque to line his coffin and go to hell. Nevertheless, while I was in France in February, the cheque duly arrived in the post. When I got back to England, I put the cheque and letter back in their envelope, wrote on it "PLS RETURN TO SENDER," trudged heavily to the postbox at the end of my road, and sent the letter back.

The truth is that what was poisoned in 1997 was not only the Nishijima-Cross translation partnership but also the mutual trust between father and son. When Gudo reacted to Mrs Luetchford's visit with his "strong refusal," it was not only that a son lost his father but also that a father lost his son.

That is why today, while listening to Desert Islands Discs and eating my breakfast, I found myself cupping my face in my hands and sobbing -- allowing Moro (II) to try to do is job of kick-starting into action a system that has long been stuck in fear paralysis/denial.

That is why, on Saturday morning when I was pointing a wall and Danny Boy came on the radio, my eyes became so blurred that I was in danger of falling off the ladder.

Tuesday, 25 March 2008

ANRAKU NO HOMON: A Dharma-Gate of Ease

Master Dogen described sitting-zen as not zen to be learned but rather ANRAKU NO HOMON.

In the Nishijima-Cross translation of 1994, this phrase is translated as "the peaceful and joyful gate of Dharma."

The purpose of this post is not to say that the former translation was necessarily wrong. AN means peace, ease, comfort. RAKU means joy, comfort, ease. HO means Dharma. MON means gate. So, as a literal translation, there is nothing seriously wrong with "the peaceful and joyful gate of Dharma."

But if true sitting-zen is a peaceful and joyful Dharma-gate, what then is this practice of mine, which is often not peaceful and joyful, but filled with immature reaction to noise, and other kinds of suffering and complaining?

A few weeks ago a person who had never met me face to face asked me on the phone, with an open mind, simply out of a desire to know, "Are you at peace with yourself?" It was a very good question.

For the past week I have been alone in France, following a routine including four sittings a day adding up to five hours (60+40) + (40+40) + (40+40) + 40. In between I do chores, and write stuff like this, and prepare and eat food, and take naps, and walk up and down admiring the trees. But the main task I set myself, selfish or obsessive-compulsive though it may sound, is to get in those four sessions of sitting-zen adding up to five hours.

So is all this sitting adorned with plentiful peace and joy?

Sometimes it is. But in general, no it is not -- not overtly, anyway, and especially not in weather as cold as it has been for the past few days.

The Buddha preached the 2nd law of thermodynamics. This law not only explains phenomena like frigid hands and chapped lips; it also explains the loss by which human life is invariably accompanied, bringing in its wake grief and suffering. Is there a mustard seed anywhere that testifies to the contrary? No, there is not.

When we suffer loss, we grieve. The bereavement does not have to be the death of a beloved person or the loss of a treasured object -- it can be the loss of another's trust or the loss of our own dream.

On what basis, then, other than the dictionary, am I, a being who frequently sits suffering in hell, to translate into English ANRAKU NO HOMON?

Only on the basis that the six samsaric realms are just the one bright pearl.

On this basis, I think that ANRAKU might be better translated as "ease" -- on the basis that, when we are sitting in hell, bereft of the peace and joy that can exist in the realms of human beings and gods, when we affirm our seat in hell and do not bother trying to make ourselves peaceful and joyful, just in that not bothering there is ease to be had.

A fellow devotee of sitting-zen asked me yesterday to express a view on compassion -- does compassion precede body and mind dropping off, or vice versa?

My response is this: Master Dogen nowhere writes that our job to have a view on compassion. He writes that our job is to devote ourselves to bodily sitting in lotus, mentally sitting in lotus, and body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting in lotus.

When we are able truly to entrust ourselves to this process of growth through sitting, even if this entrustment takes us in recurring cycles to hell and back, even if our practice becomes temporarily devoid of peace and joy, even then there is ease to be had, just in the act of entrustment itself.

In the Nishijima-Cross translation of 1994, this phrase is translated as "the peaceful and joyful gate of Dharma."

The purpose of this post is not to say that the former translation was necessarily wrong. AN means peace, ease, comfort. RAKU means joy, comfort, ease. HO means Dharma. MON means gate. So, as a literal translation, there is nothing seriously wrong with "the peaceful and joyful gate of Dharma."

But if true sitting-zen is a peaceful and joyful Dharma-gate, what then is this practice of mine, which is often not peaceful and joyful, but filled with immature reaction to noise, and other kinds of suffering and complaining?

A few weeks ago a person who had never met me face to face asked me on the phone, with an open mind, simply out of a desire to know, "Are you at peace with yourself?" It was a very good question.

For the past week I have been alone in France, following a routine including four sittings a day adding up to five hours (60+40) + (40+40) + (40+40) + 40. In between I do chores, and write stuff like this, and prepare and eat food, and take naps, and walk up and down admiring the trees. But the main task I set myself, selfish or obsessive-compulsive though it may sound, is to get in those four sessions of sitting-zen adding up to five hours.

So is all this sitting adorned with plentiful peace and joy?

Sometimes it is. But in general, no it is not -- not overtly, anyway, and especially not in weather as cold as it has been for the past few days.

The Buddha preached the 2nd law of thermodynamics. This law not only explains phenomena like frigid hands and chapped lips; it also explains the loss by which human life is invariably accompanied, bringing in its wake grief and suffering. Is there a mustard seed anywhere that testifies to the contrary? No, there is not.

When we suffer loss, we grieve. The bereavement does not have to be the death of a beloved person or the loss of a treasured object -- it can be the loss of another's trust or the loss of our own dream.

On what basis, then, other than the dictionary, am I, a being who frequently sits suffering in hell, to translate into English ANRAKU NO HOMON?

Only on the basis that the six samsaric realms are just the one bright pearl.

On this basis, I think that ANRAKU might be better translated as "ease" -- on the basis that, when we are sitting in hell, bereft of the peace and joy that can exist in the realms of human beings and gods, when we affirm our seat in hell and do not bother trying to make ourselves peaceful and joyful, just in that not bothering there is ease to be had.

A fellow devotee of sitting-zen asked me yesterday to express a view on compassion -- does compassion precede body and mind dropping off, or vice versa?

My response is this: Master Dogen nowhere writes that our job to have a view on compassion. He writes that our job is to devote ourselves to bodily sitting in lotus, mentally sitting in lotus, and body-and-mind-dropping-off sitting in lotus.

When we are able truly to entrust ourselves to this process of growth through sitting, even if this entrustment takes us in recurring cycles to hell and back, even if our practice becomes temporarily devoid of peace and joy, even then there is ease to be had, just in the act of entrustment itself.

Sunday, 23 March 2008

HISHIRYO: Non-Thinking (2)

Fixing in the view that HISHIRYO means "[Action which] is different from thinking," is one hell of a mistake. I know, because I made that mistake, well and truly, and therein believed myself to be firmly on the side of the righteous.

By fixing in the view that HISHIRYO means action itself which is different from thinking, it seems to me now, I turned one face of the truth of HISHIRYO into its dialectical opposite. I turned the pursuit of individual freedom into rigid adherence to a view espoused by a teacher.

If the fixed view is right that HISHRYO means action which is different from thinking, then every irrational act of group violence committed by human beings, every war atrocity, should be praised as HISHIRYO.

If the fixed view is right that HISHRYO means action which is different from thinking, then every animalistic act of group rape and every intellect-transcending baton-charge, should be praised as HISHIRYO: "Come on, man, just do it!" "1,2,3 -- Go!"

FM Alexander was a champion of individual freedom and a despiser of mindless group behaviour -- the latter being exemplified for him by Germany's actions in two world wars. As a man who despised mindless group behaviour based on the herd instinct, FM used to say, "This work is an exercise in finding out what thinking is."

He also used to say to his teacher-trainees, "None of you knows that thinking is."

After I returned to England to train as an Alexander teacher, but before I actually started training, I attended, in the summer of 1995, a lecture given by Marjory Barlow on the subject of Thinking. Marjory, in that lecture and in subsequent one-to-one lessons that she gave me, took pains to impress on me that Alexander work was not, as people commonly misunderstand it to be, a kind of bodywork. It is rather, "the most mental thing there is."

As I began to understand this, from 1995 onward, I initiated a long and vigorous philosophical exchange with Gudo (via email) on the subject of HISHIRYO. I challenged his teaching that HISHIRYO means "[Action which] is different from thinking." In return, he accused me of showing the intellectual attitude which is typical of the caucasian intellectual (as opposed to the practical yellow man). In this accusation I sensed a remnant of the propaganda booklet that was given to all officers of the Japanese Imperial Army in World War II, identifying the enemy as HAKUJIN NO BUNKA, "white man's civilization" -- intellectual civilization.

In retrospect, with the benefit of ten years or so experience struggling to deepen my understanding of what Alexander meant by thinking, I would say that Gudo and I were both wrong; we were both wrongly fixed in our respective views. We were both stuck in a mode of being favoured by the control freak -- "I know; you don't."

When I went to Japan for a few weeks in the summer of 1998, after finishing Alexander teacher training, Gudo told me over breakfast in the Zazen Dojo that he thought I might understand his teaching "in tens of years." In response, in anger, I picked up a piece of crockery and threw it onto the ground, shattering it to smitherines, and said: "There. That is action!"

Afterwards I telephoned him at his office to apologize for my angry behaviour. My rage, I see with hindsight, was just another example of the mirror principle. Gudo, with his "I know; you don't know" attitude, was holding up a mirror to a fellow control-freak. Anyway, when I apologized for my angry behaviour, Gudo said that he affirmed what I had done. "You acted, for the first time in your life," he told me.

Frankly, that interpretation of the event was a load of bollocks. What happened was that, in my frustration at not being able to win an argument with a fellow fixed-viewed know-it-all, I flew into a rage and broke a pot.

Though I had heard Alexander's words that "None of you knows what thinking is," I somehow wasn't open enough, I somehow lacked the humility, to really take on board that those words might apply to me. So I argued with Gudo on the basis that I knew what HISHIRYO was, whereas he didn't. But that was not even half true.

Back in the 1980s, having resigned myself to a life of struggle in Tokyo, I used to read in Shobogenzo of Taiso Eka cutting off his arm in the snow, or Zen masters living in the mountains with only two or three disciples because the conditions were so harsh that not many could endure it. And I used to think to myself: "those lucky bastards."

During one complaining session before Gudo, in his office in Ichigaya, he stopped my grumbling by saying, "Your suffering has meaning for all people in the world."

Mmmmm. Recently Shobogenzo Book 1 has been re-printed by Numata, and a very nice job they seem to have done with it too. I had nothing to do with this re-printing. I left negotiations entirely to Gudo. I suppose it must be him that I have to thank for my biography being abbreviated to three lines, ending with the statement that I returned to England in 1994.

This would be in accordance with the view expressed by Gudo that after returning to England I strayed back into intellectualism and became a non-Buddhist out to identify Master Dogen's teaching with "AT theory." According to that view, my suffering had meaning for all people in the world, insofar as I continued to do Gudo's donkey work for him in Japan, whereas the suffering I have endured through doubting and opposing my master's teaching of HISHIRYO might not have any meaning for all people in the world.

I still seem to be suffering, and I must confess that I miss the reassurance of being told that my suffering has meaning for all people in the world. I can tell it to myself, mentally, but somehow it doesn't seem to resonate so convincingly like that.

Speaking of herd instinct vs HISHIRYO, there are those within the Tibetan exile community, it seems, who argue that violent group action would be an effective means of achieving their political aim of a free Tibet. I think that the Dalai Lama's response to this might be a response that arises out of the practice of HISHIRYO.

The Buddha's teaching of HISHIRYO might not originally be for the purpose of achieving political aims. It might rather be for the purpose of pursuing individual freedom -- and not freedom in the abstract, but freedom of the neck, to let ears and shoulders oppose each other, and let the nose and navel oppose each other.

What then, in the end, is HISHIRYO?

Is it action which is different from thinking, as per the Nishijima-Cross translation?

No, it is not that. That is a view into which I stray as if I were a blind donkey.

Is it thinking, but not what people generally think of as thinking, as discussed by Alexander?

No, it is not that. That is a view into which I stray as if I were a god.

To practice HISHIRYO as action which is different from thinking -- sticking in the view that HISHIRYO means action as opposed to thinking -- is a mistake. It is a mistake like sitting in full lotus with the body.

To practice HISHIRYO as thinking which is opposed to instinctive/habitual/feeling-based doing -- sticking in the view that HISHIRYO means thinking but not what people generally think of as thinking -- is also a mistake. It is a mistake like sitting in full lotus with the mind.

As a result of making mistakes like this, a father loses a son and a son loses a father. Whether Gudo Nishijima comes out of hospital again or not won't make much difference to my grieving process, which began, with fear paralysis/shock/denial, back in 1997.

Finally I shall finish this post by endeavoring to answer some questions somebody asked me offline:

What does Master Dogen mean by "body and mind dropping off"?

For example, he means wholeheartedly pursuing the Buddha's truth of anuttara-samyak-sambodhi through the practice of sitting-zen, not worrying about how many times we fall into hell along the way, not being afraid of making mistakes, not trying to hide the fact that I, like everybody else with an imperfect vestibular system, can't stop being a control freak; Master Dogen means, in short, because of the supreme value of the Buddha's truth, forgetting the small self.

When it happens to us do we know it? Does it come to us? Do we go towards it?

I think that when something along those lines happens to me during sitting-zen, sometimes I experience an enjoyable deep breath that seems to go right down into the sitting-cushion. Or sometimes, outside of sitting-zen itself, I am struck by the perfection of some natural phenomenon, like a birdsong or sunlight on the trees or the yellow moon in the night sky. Or the white moon in the blue sky.

At such times, we are not self-conscious of "body and mind dropping off," because there is no such thing.

Yes, those experiences come to us -- we become as if a target that is hit.

Yes, we tend to go towards those experiences. We sit or stand there with daft, intense expressions on our faces, expecting and trying to recapture them -- which is just the essence of deluded control-freakery.

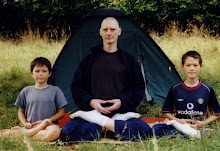

Passers-by -- people walking through the forest, for example -- when they notice us practising are liable to think that we are somewhat odd.

By fixing in the view that HISHIRYO means action itself which is different from thinking, it seems to me now, I turned one face of the truth of HISHIRYO into its dialectical opposite. I turned the pursuit of individual freedom into rigid adherence to a view espoused by a teacher.

If the fixed view is right that HISHRYO means action which is different from thinking, then every irrational act of group violence committed by human beings, every war atrocity, should be praised as HISHIRYO.

If the fixed view is right that HISHRYO means action which is different from thinking, then every animalistic act of group rape and every intellect-transcending baton-charge, should be praised as HISHIRYO: "Come on, man, just do it!" "1,2,3 -- Go!"

FM Alexander was a champion of individual freedom and a despiser of mindless group behaviour -- the latter being exemplified for him by Germany's actions in two world wars. As a man who despised mindless group behaviour based on the herd instinct, FM used to say, "This work is an exercise in finding out what thinking is."

He also used to say to his teacher-trainees, "None of you knows that thinking is."

After I returned to England to train as an Alexander teacher, but before I actually started training, I attended, in the summer of 1995, a lecture given by Marjory Barlow on the subject of Thinking. Marjory, in that lecture and in subsequent one-to-one lessons that she gave me, took pains to impress on me that Alexander work was not, as people commonly misunderstand it to be, a kind of bodywork. It is rather, "the most mental thing there is."

As I began to understand this, from 1995 onward, I initiated a long and vigorous philosophical exchange with Gudo (via email) on the subject of HISHIRYO. I challenged his teaching that HISHIRYO means "[Action which] is different from thinking." In return, he accused me of showing the intellectual attitude which is typical of the caucasian intellectual (as opposed to the practical yellow man). In this accusation I sensed a remnant of the propaganda booklet that was given to all officers of the Japanese Imperial Army in World War II, identifying the enemy as HAKUJIN NO BUNKA, "white man's civilization" -- intellectual civilization.

In retrospect, with the benefit of ten years or so experience struggling to deepen my understanding of what Alexander meant by thinking, I would say that Gudo and I were both wrong; we were both wrongly fixed in our respective views. We were both stuck in a mode of being favoured by the control freak -- "I know; you don't."

When I went to Japan for a few weeks in the summer of 1998, after finishing Alexander teacher training, Gudo told me over breakfast in the Zazen Dojo that he thought I might understand his teaching "in tens of years." In response, in anger, I picked up a piece of crockery and threw it onto the ground, shattering it to smitherines, and said: "There. That is action!"

Afterwards I telephoned him at his office to apologize for my angry behaviour. My rage, I see with hindsight, was just another example of the mirror principle. Gudo, with his "I know; you don't know" attitude, was holding up a mirror to a fellow control-freak. Anyway, when I apologized for my angry behaviour, Gudo said that he affirmed what I had done. "You acted, for the first time in your life," he told me.

Frankly, that interpretation of the event was a load of bollocks. What happened was that, in my frustration at not being able to win an argument with a fellow fixed-viewed know-it-all, I flew into a rage and broke a pot.

Though I had heard Alexander's words that "None of you knows what thinking is," I somehow wasn't open enough, I somehow lacked the humility, to really take on board that those words might apply to me. So I argued with Gudo on the basis that I knew what HISHIRYO was, whereas he didn't. But that was not even half true.

Back in the 1980s, having resigned myself to a life of struggle in Tokyo, I used to read in Shobogenzo of Taiso Eka cutting off his arm in the snow, or Zen masters living in the mountains with only two or three disciples because the conditions were so harsh that not many could endure it. And I used to think to myself: "those lucky bastards."

During one complaining session before Gudo, in his office in Ichigaya, he stopped my grumbling by saying, "Your suffering has meaning for all people in the world."

Mmmmm. Recently Shobogenzo Book 1 has been re-printed by Numata, and a very nice job they seem to have done with it too. I had nothing to do with this re-printing. I left negotiations entirely to Gudo. I suppose it must be him that I have to thank for my biography being abbreviated to three lines, ending with the statement that I returned to England in 1994.

This would be in accordance with the view expressed by Gudo that after returning to England I strayed back into intellectualism and became a non-Buddhist out to identify Master Dogen's teaching with "AT theory." According to that view, my suffering had meaning for all people in the world, insofar as I continued to do Gudo's donkey work for him in Japan, whereas the suffering I have endured through doubting and opposing my master's teaching of HISHIRYO might not have any meaning for all people in the world.

I still seem to be suffering, and I must confess that I miss the reassurance of being told that my suffering has meaning for all people in the world. I can tell it to myself, mentally, but somehow it doesn't seem to resonate so convincingly like that.

Speaking of herd instinct vs HISHIRYO, there are those within the Tibetan exile community, it seems, who argue that violent group action would be an effective means of achieving their political aim of a free Tibet. I think that the Dalai Lama's response to this might be a response that arises out of the practice of HISHIRYO.

The Buddha's teaching of HISHIRYO might not originally be for the purpose of achieving political aims. It might rather be for the purpose of pursuing individual freedom -- and not freedom in the abstract, but freedom of the neck, to let ears and shoulders oppose each other, and let the nose and navel oppose each other.

What then, in the end, is HISHIRYO?

Is it action which is different from thinking, as per the Nishijima-Cross translation?

No, it is not that. That is a view into which I stray as if I were a blind donkey.

Is it thinking, but not what people generally think of as thinking, as discussed by Alexander?

No, it is not that. That is a view into which I stray as if I were a god.

To practice HISHIRYO as action which is different from thinking -- sticking in the view that HISHIRYO means action as opposed to thinking -- is a mistake. It is a mistake like sitting in full lotus with the body.

To practice HISHIRYO as thinking which is opposed to instinctive/habitual/feeling-based doing -- sticking in the view that HISHIRYO means thinking but not what people generally think of as thinking -- is also a mistake. It is a mistake like sitting in full lotus with the mind.

As a result of making mistakes like this, a father loses a son and a son loses a father. Whether Gudo Nishijima comes out of hospital again or not won't make much difference to my grieving process, which began, with fear paralysis/shock/denial, back in 1997.

Finally I shall finish this post by endeavoring to answer some questions somebody asked me offline:

What does Master Dogen mean by "body and mind dropping off"?

For example, he means wholeheartedly pursuing the Buddha's truth of anuttara-samyak-sambodhi through the practice of sitting-zen, not worrying about how many times we fall into hell along the way, not being afraid of making mistakes, not trying to hide the fact that I, like everybody else with an imperfect vestibular system, can't stop being a control freak; Master Dogen means, in short, because of the supreme value of the Buddha's truth, forgetting the small self.

When it happens to us do we know it? Does it come to us? Do we go towards it?

I think that when something along those lines happens to me during sitting-zen, sometimes I experience an enjoyable deep breath that seems to go right down into the sitting-cushion. Or sometimes, outside of sitting-zen itself, I am struck by the perfection of some natural phenomenon, like a birdsong or sunlight on the trees or the yellow moon in the night sky. Or the white moon in the blue sky.

At such times, we are not self-conscious of "body and mind dropping off," because there is no such thing.

Yes, those experiences come to us -- we become as if a target that is hit.

Yes, we tend to go towards those experiences. We sit or stand there with daft, intense expressions on our faces, expecting and trying to recapture them -- which is just the essence of deluded control-freakery.

Passers-by -- people walking through the forest, for example -- when they notice us practising are liable to think that we are somewhat odd.

Thursday, 20 March 2008

SUNAWACHI SHOSHIN TANZA

SUNAWACHI means just, at once, immediately. SHO means rectify, straighten out. SHIN means the body, the person, the actual self. TANZA means sit up, sit erect.

So the instruction which is at the centre of Master Dogen's instructions for sitting-zen, SUNAWACHI SHOSHIN TANZA, means "Just sit up straight."

Failing to translate these words according to Master Dogen's true intention has been, for more than half of my 48 years, the greatest and most fundamental wrongness in my life -- all other mistakes have been twigs and leaves. If being wrong is the best friend I have got, these were the words that introduced me to my best friend: SUNAWACHI SHOSHIN TANZA, "Just sit up straight."

Some stupid people in the world of education refuse to see dyslexia (from the Greek dys- difficulty + lexia, reading) as a vestibular problem. They sometimes describe it as a "cognitive deficit." But dyslexic children -- at least the dyslexic children we have helped over the years at the Middle Way Re-education Centre -- invariably have underlying dysfunction deep in their vestibular system.

Some children with deep vestibular dysfunction, paradoxically, are hyperlexic. This phenomenon probably has something to do with the capacity of higher parts of the brain to compensate for underlying weaknesses. So some children we see, while they struggle with basic balance and coordination, for example, use vocabulary you would expect from much older children.

Compensation produces paradoxical results. Einstein, for example, may have been a bit dyslexic. Or maybe he was a lot dyslexic. Again, the most powerful punch I have ever witnessed belonged to a teacher from Okinawa who was encouraged to take up karate-do because he was so weak and sickly as a child.

Nobody ever accused me of having a cognitive deficit when I was growing up -- at the age of five or six, my reading was more advanced than other children in my own year and also in the year above. I was often accused of having no common sense, though, and of tending to take things too far. At one parents' evening, when I was eight, a certain Miss Whittle told my parents: "Michael is very bright, but his behaviour is disgusting." Tell it like it is, Miss W.

Later on my precociousness was dimmed, partly as a result of skipping a year between primary and secondary school, and possibly also as a result of taking at an early age to the bottle -- from the age of 13 I started making home-brew beer and drinking it in large quantities with my mate from over the road. No longer ahead of the game at reading, I certainly got ahead of the game at drinking.

But back in primary school, where the foundations for over-confidence in my own intellectual ability were laid, I was generally top of the class. Miss Higgins, whose class I attended aged nine, used to give us a problem to solve every morning. The first one to solve it would be noted and at the end of the week a little present -- a boiled sweet or something -- would be given to the champion for that week. Miss Higgins, who I liked a lot better than the younger, mini-skirted Miss Whittle, made a rule that I was only allowed to win every other week.

From this and similar experiences, I picked up confidence in my ability to work out, to think out, solutions to practical problems -- providing that (1) the parameters to the particular problem had been clearly set for me, that (2) I had been given all the information needed to solve the problem, and that (3) I was motivated to solve it.

For a few years at least, those three conditions were all met in my work under Gudo to translate Shobogenzo into English -- before, that is, certain jealous individuals, as if from a Shakespearian tragedy, intervened to poison the process and knock out condition (3).

Sorry if I seem to dwell on this poisoning metaphor, but for me it represents something of a realization.

From the autumn of 1987 to the spring of 1988 I lived non-stop in the Ida Zazen Dojo in Moto-yawata, for the first six months since its establishment. By that time my problem-solving brain had already deduced from the information presented in Shobogenzo that Master Dogen's teaching all boiled down to sitting-zen, and the essential instruction for sitting-zen was just to sit up straight. That deduction still seems to me to be true -- nothing has falsified it yet. Where I have gone so badly wrong, where my lack of common sense has come into play, is in my efforts to translate the words "sit up straight" into action.

In those first six months of the Zazen Dojo, for example, I tried -- with great intensity, great seriousness, great rigidity -- to sit up as straight and for as long as possible, for five, six, seven, eight, nine or ten hours a day. The more difficult life at the Dojo seemed to get, the more intense, serious, and rigid I got in my effort to sit up straight. My health began to deteriorate, as did my relations with the other members of the Dojo, who I had presumed to lead in practice. After one incident, during which I shouted loudly at another member of the Dojo, Gudo summoned us both to his office, and asked me to apologize, which I did. After that he offered to transmit the Dharma to me. As far as I know, it was the first time he offered to transmit the Dharma to anybody. I suppose he could see the extent to which I was struggling, and wanted to help me. From my side, I didn't have the confidence to accept. It was not like nowadays when everybody and his dog seems to be receiving the Dharma. To receive the Dharma, at that time, seemed to me to be such a big deal that I couldn't conceive of myself being up to the task of receiving it. In particular, I was worried about whether or not I could remain celibate. Gudo himself had given up sexual relations with his wife before receiving the Dharma, so I assumed it was a prerequisite.

While I was struggling at the Dojo, Gudo recommended me not to leave. He told me that he had built the Dojo for me, and reminded me of Master Dogen's teaching of FURI-SORIN, not leaving the monastery. But in the end it was obvious to all that I had to go. The majority of other members of the Dojo wanted me to go, and eventually I went. For a couple of weeks my old friend and mentor David Essoyan put me up with his young family in his flat in Tokyo, then I went to Thailand and spent a couple of weeks at Wat Pah Nanachat, and a few weeks coming and going at a big Wat in Bangkok whose name eludes me now. Then I went back to England for a couple of weeks. Then the wheel of samsara turned decisively, and I moved from the realm of hungry ghost into the asura realm. I determined to go back to Japan and throw myself in earnest into the Shobogenzo translation.

When I got back to Tokyo, Gudo gave me a letter he had written and taken in vain to the Thai embassy in Tokyo. Worried that the life of a Thai monk would suit me, he expressed in the letter his hope that we would work together in earnest on the Shobogenzo translation, and asked me for five years. The letter didn't make any difference, as I had already made up my mind what I was going to do.

From that time, the early summer of 1988 through till around the time in 1997 when Yoko Luetchford visited Gudo at his office and reported my alleged plot to use the Shobogenzo translation to identify Buddhism and AT, Gudo paid me a monthly 'scholarship' of 50,000 yen. That money meant a lot to me, not only financially but also emotionally. When the scholarship suddenly stopped in 1997, while I was doing my Alexander teacher training in England while still working on the revision of Shobogenzo Book 4, I couldn't understand why. Around the same time I received a strange letter from Gudo expressing his hope that I would "come back to Buddhism." Since I knew perfectly well in my own mind that nothing had changed in my devotion to sitting-zen, four times a day, as usual, I didn't really worry about this strange letter.

Then in the summer of 1997, Jeremy Pearson, on a trip back to England from Japan, visited me in Aylesbury. We got talking about the meaning of BUTSU KOJO NO JI, the matter of buddha ascending beyond, and I told Jeremy how Alexander work had caused me to look for a more dynamic translation of the phrase -- i.e. "the continuing upwardness of buddha." Then Jeremy casually dropped the bomb. "Oh, I changed that."

When I phoned Michael Luetchford to enquire what the hell had happened, Luetchford told me, "I am the publisher. I can do what I want." The scheming Sanzo, it seemed to me then, had waited his moment, and turned me over.

After that I stopped work on Shobogenzo. My wife shed buckets of tears. Why shouldn't she? Anybody who knew the sacrifices I asked her to make so that I could work on the Shobogenzo translation would not be surprised that she shed tears. I, however, didn't shed a tear. My perception was that war had been declared, and it was a war I had the means to win, by sitting in the full lotus posture, and translating into action the essential instruction for that sitting: SUNAWACHI SHOSHIN TANZA -- Just sit up straight.

And therein lay the problem. I had the right idea, I have the right idea, but in my attempts to translate the idea into action, what happens? I am tripped up by trying to be right, which ties me to reliance on a dysfunctional vestibular system. What feels straight to me, what feels right to me, is wrong. So, by trying to be right, I make myself even more wrong.

In trying to live up to Gudo's expectations for me, of being champion of Dogen Sangha, his rightful successor, the most excellent Buddhist master in the world, I have become an outcast from Dogen Sangha, a Zen bastard, Mr Wrong, a voice in the wilderness.

In so becoming, what have I learned? In so having become, what have I got to offer?

In a comments to a previous post, I mentioned my love of human (as opposed to celestial) beings. My brother pointed out that while I may love human beings in theory, in practice I am generally happiest when there are none around. Back on my own again in France, I realize what my brother said is true. I prefer to express my love for human beings from afar. When among human beings, I generally find them to be a pain in the arse. That being so, thank God for Google, thank God for this vehicle which allows my voice in the wilderness to be heard. Thank God for this chance for me to let others know what, without any shadow of a doubt, I have learned: