Truly, the path to hell is paved with such intentions.

What makes a human truly human? Some would say it is language, in which case the vital thing might be the areas of the brain and body devoted to speech and language. Some have said that the ability to use the hands to make tools was vital to the evolution of our species.

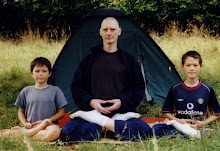

But sitting upright in the lotus posture, with ease and in stillness, does not involve either speech or manufacturing production. No, for this particular sphere of activity the vital thing might be human upright balance, for which evolution has equipped us with eyes, ears, and the sense organs of proprioception (muscle spindles, Golgi tendon organs, and joint receptors), input from all of which is integrated, for better or for worse, by our vestibular system.

A vestibular reflex discussed earlier, the symmetrical tonic neck reflex (STNR), is exhibited not only by human beings from the age of about 6 months, but also by animals like cats, dogs and monkeys. The thing that makes human beings different from monkeys, from a postural point of view, is the ability of at least some of us to inhibit the STNR.

Going into a position of standing like a monkey, with the neck extended while hips and knees remain flexed, can help a person's vestibular system get re-acquainted with the STNR. Only when the vestibular system has been thoroughly acquainted with the STNR: only then can a person manifest inhibition of the STNR, by standing and walking truly upright -- neck, hips, and knees all effortlessly extended, without strain.

At this point in the discussion, I must pause, again, and ask if anybody fancies joining me for a banana? Or how about a peanut?

Inhibition of the STNR, in the natural course of an infant's development, is accomplished basically by movements, the messages for which are hard-wired deep in the infant's brain. Rocking back and forward on hands and knees, for example, facilitates inhibition of the STNR. Or, for another example, performing prostrations facilitates inhibition of the STNR.

These movements performed on hands and knees, whether performed instinctively or consciously, via hard-wiring or enlightened intention, facilitate physiological inhibition of the vestibular reflex.

Ray Evans was a human being with deep insight into the importance of the vestibular system, and the associated problem that FM Alexander identified as "faulty sensory appreciation."

It is because of faulty sensory appreciation that good intentions pave the way to hell.

On the basis of his deep insight, Ray introduced me to the field of work that he sometimes used to call "vestibular re-education." Alexander himself originally called it "Man's Supreme Inheritance." Alexander's first book was titled: Man's Supreme Inheritance -- Conscious Guidance and Control in Relation to Human Evolution in Civilization.

Alexander, you see, from the very beginning, consciously introduced consciousness into the picture. He knew that his work, though it addressed the vestibular-based problem of faulty sensory appreciation, was "the most mental thing there is."

The vestibular system, at brainstem level, is not only at the centre of processing balance-related sensory input from eyes, ears, skin, muscle spindles, et cetera; it is also integrates information coming from other sensory-processing centres, such as the cerebellum.

Detailed discussion of brain anatomy is a minefield I do not wish to enter. But this much I do know, from karate training onward: the cerebellum can be consciously re-trained.

The point I am driving at is this: the vestibular system is susceptible to re-education not only via movement and non-movement but also, within the context of movement and non-movement, via clarity of intention. Human upright balance is not a purely instinctive thing but is also a function of intelligence. The backward step to a condition of greater ease and stillness in upright sitting, CAN BE LEARNED.

Clearly understanding the need for re-education of the vestibular system, through learning how to think, Ray Evans often used to say, "Human beings have not yet learned to think in this way."

By "thinking," Ray meant something other than doing based on feeling, and something other than intellectual thinking.

Alexander work involves what is called in Alexander shorthand "thinking up." Thinking up involves a kind of evolutionary leap from reliance on purely reflex mechanisms of upright balance, which are liable to be faulty. Thinking up doesn't mean thinking about something; it means thinking itself, which is not what people think of as thinking. So maybe this new kind of thinking should not be called "thinking" at all. Maybe it should be called instead "non-thinking."

"Non-thinking." Hmmm. Where have I come across that phrase before?

What "non-thinking" is, I honestly don't know. As the years go by, I hope that I gain, bit by bit, more clarity in regard to what it isn't. That is to say, I hope I understand more clearly that non-thinking is neither doing based on feeling, nor intellectual thinking. Whatever I think "non-thinking" is, it is always not that.

Quad Erat Demonstrandum.

No comments:

Post a Comment